Why EdTech’s hero complex kills startups and how Amanda Goodson built Edlink through hypothesis testing, cold outreach, and boring problems.

Most EdTech founders want to star in The Social Network.

They’re actually in The Office.

Lots of waiting around, awkward small talk with decision-makers, and realizing the real work happens in unglamorous back rooms where nobody’s making documentaries. The harsh reality is 60% percent of EdTech startups fail, and most of them die chasing the same Hollywood dream: becoming the hero who saves education.

Amanda Goodson, co-founder and COO of Edlink, learned this lesson while building her B2B integration platform from Austin, Texas without a single warm introduction.

Instead of trying to “revolutionize” learning, she focused on the boring stuff that actually matters—connecting Student Information Systems to Learning Management Systems.

“When I first came into EdTech,” Amanda recalls, “I had the impression that you had to have a Rolodex to do this, and I didn’t.” Now Edlink serves major companies like Carnegie Learning and over 100 school districts, all because she chose to solve practical problems over selling glamorous narratives.

Key Takeaways

- Most EdTech companies fail because they chase hero narratives instead of solving mundane but critical operational problems

- Success comes from hypothesis-driven market validation with paying customers, not enthusiastic feedback from warm networks

- The most sustainable EdTech businesses focus on boring infrastructure solutions rather than revolutionary learning platforms

The industry’s hero complex is killing real progress

EdTech has a blindspot about what success looks like.

Many operate under the dangerous assumption that a new EdTech company needs a high-flying vision to capture the interest of superintendents and a contact list full of administrators to build something meaningful. This creates a culture where founders prioritize being perceived as educational revolutionaries over addressing the unglamorous operational challenges that actually prevent schools from functioning efficiently.

Amanda discovered this firsthand when she entered EdTech.

Most companies chase what feels important instead of what schools actually need. They want to be featured in EdSurge articles about “transforming learning.” It’s not as fun to solve the data integration nightmares that started in the ‘70s. The market is flooded with blue-sky ideas, and very few people who understand how to implement the solutions.

The stakes are real. While founders burn through funding forcing a square peg into a round hole, schools struggle with basic tech infrastructure that doesn’t talk to itself. Students sit in classes where teachers manually enter the same attendance data into three different systems. Districts spend countless hours on workarounds for problems that could be solved with boring, reliable integration tools.

It’s creating a massive opportunity gap. The companies that recognize that “revolutionary” often means “reliably functional” are the ones building sustainable businesses while their competition chases unicorn valuations.

The anti-glamour validation engine

Amanda’s success comes from treating EdTech like any other business, not a mission-driven crusade. Her framework centers on systematic hypothesis testing rather than assuming educators would love whatever she built..

Prepwork: Form the hypothesis

Start with a specific problem hypothesis that people will pay to solve.

Amanda’s team didn’t guess what schools needed: “We formed a hypothesis that there was this certain problem that we would be able to solve,” she explains. ”And that people who experienced that problem would pay money for it.”

Once she had a clear hypothesis, the real work began. And she had to be willing to fail. Amanda’s validation engine operated as a continuous four-stage cycle that either proved the assumption or would have forced her to form a better one:

- Stage 1: Test through cold outreach

Amanda skipped the warm network entirely. “Everything was cold outreach,” she says. “We didn’t start visiting conferences until year two or three.” Cold outreach cuts through the politeness problem. When strangers validate the idea, it’s the solution talking, not just a charming personality. It forces a company to articulate value to strangers who owe them nothing. - Stage 2: Follow with money

Let’s face it:nice words don’t pay the bills. When Edlink was transitioning clients from their previous company, customers kept asking if they could buy just the integration tools, not giving polite feedback or feigned interest. These were IT directors pulling out their procurement budgets, pointing to a specific piece of functionality, and asking “How much for that part?” When customers identify exactly what’s solving their problem and volunteer to pay for it separately, a company has validated the hypothesis. - Stage 3: Refine against the original hypothesis

Edlink stayed disciplined about the core assumption. “I think people get into trouble when they stray from their hypothesis and just say yes to everything.” Feature requests that pull away from the validated problem is a potential death sentence. Success comes from going deeper on what works, not broader on what sounds interesting. - Stage 4: Scale through systems, not relationships

Build repeatable processes, not relationship-dependent sales. The companies that survive long-term create systems that work without the founder’s personal network. This means documented sales processes, product-market fit that speaks for itself, and customer success that doesn’t require constant hand-holding.

Extra Credit: Find the sweet spot via two axes

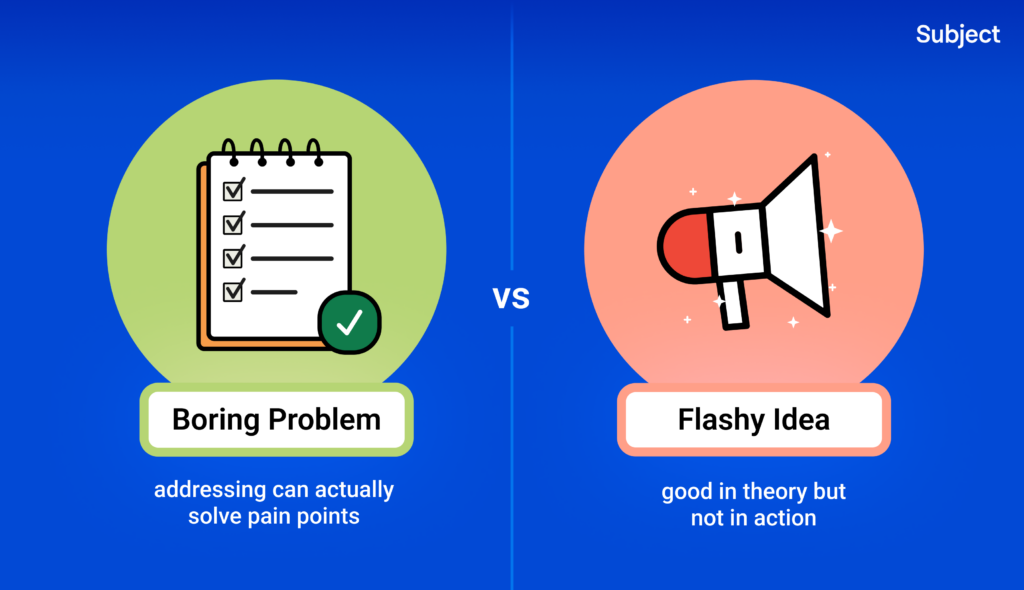

Amanda plots each validation cycle on two axes: “Boring vs. Sexy” (how glamorous the solution appears) and “Praised vs. Paid” (whether customers actually pay or just give feedback). The sweet spot is Boring + Paid, where Amanda found success with integrations. The danger zone is Sexy + Praised, where most EdTech companies get trapped chasing solutions that sound revolutionary but don’t solve daily operational problems.

The engine keeps spinning. Each cycle generates data to refine the hypothesis and move toward solutions people actually pay for, not just praise. Our CEO Michael Vilardo followed a similar method to build Subject.

The integration problem will only get worse

Amanda’s validation engine works because she picked the right kind of problem to solve.

Most EdTech founders chase “flashy” problems that get press coverage. Amanda went the opposite direction. She looked for the stuff that makes school IT administrators groan and stay late on Fridays. The mundane operational headaches that don’t make headlines but eat up everyone’s time.

Integration problems between school systems are getting worse, not better. Every time a district adds a new app, they create more data silos. Teachers end up entering the same student information into three different platforms. IT staff spend hours manually moving data that should talk to itself automatically.

The funding crunch hitting EdTech (down to decade-lows) actually proves Amanda’s point. While trendy AI learning platforms struggle to find investors, the companies solving basic infrastructure problems are getting renewed interest. Turns out sustainable businesses fix the stuff that breaks every day, not the stuff that only sounds cool.

Schools are also getting smarter about vendor selection. They’re prioritizing tools that play nice with their existing systems over standalone solutions that create more complexity. The districts that survived budget cuts did it by choosing fewer tools that work better together.

This creates a massive opportunity for the companies willing to be boring. While everyone else is fighting over the “revolutionary learning platform” market, there’s wide-open space in the “make our current tools actually work” market.

Hot takes on anti-glamour success

Amanda’s contrarian principles fly in the face of Silicon Valley EdTech wisdom.

Schools are also getting smarter about vendor relationships. They’re prioritizing tools that integrate with existing systems over standalone solutions that create more complexity—on top of following other unconventional wisdom:

- Boring problems > flashy solutions: The most successful EdTech companies solve mundane daily operations, and supporting infrastructure that makes the school run. Think more “Marie Kondo organizing the school’s digital closet” and less “Steve Jobs keynote about the future of learning.”

The EdTech graveyard is full of founders who thought they were too visionary to focus on how to help schools. Amanda proved that sustainable success comes from serving schools as they actually exist, not as Silicon Valley dreams they should be. While competitors chase unicorn valuations and “revolutionary” narratives, the real opportunity lies in solving the mundane infrastructure challenges that keep educators up at night.

An education hypothesis doesn’t need to change the world. It just needs to change a teacher’s workday for the better.

To learn more about Amanda and EdLink’s work, tune in to our On the Subject episode with her.