Arts educators face a difficult balance when more students sign up for their classes. Growing a program should not mean losing the personal touch that makes arts education magical.

Jack Aron, music educator at Culver City High School, started from 20 students in a Zoom room during COVID, and now has over 100 music production students. Without sacrificing the individual attention that sparked their creativity in the first place.

Jack, who holds dual degrees in Music Composition and Music Education from UCLA, built his program around an important insight: student peer mentoring enhances individual creativity.

“I definitely pride myself as a teacher on reaching out to individual students daily,” Jack explains.

“When I mention I have 100-plus students, I like to say it’s impossible to teach music production without hearing what each individual student brings to the table.”

The secret behind his perfect pitch wasn’t restricting sign-ups or standardizing curriculum. Instead, he pulled from social learning systems that mirror how professional creative communities actually work—where experienced artists mentor newcomers while pursuing their own artistic vision.

Think less “American Idol judge panel,” more “blues jam session.”

Schools Think Scaling Kills Creative Connection

Music program directors face the same choice around class sizes that all teachers deal with. The difference for them is that they are elective classes, so there is a choice between: stay small and intimate, or grow large and impersonal.

For a larger program, the easy answer is reducing personalized instruction and pivoting to standardized assignments. Students can then lose the spark that makes creative education worthwhile.

“Teaching composition is very personal, and it’s very vulnerable for students,” Jack notes. “They want you to hear what they have to say, and they want you to lean in and tell them, ‘Hey, this is really good work,’ and give them encouragement.” Teachers need time to give that personalized attention while helping students learn how to build their own creative community.

When programs standardize creative instruction, students lose the chance to develop their unique artistic voice within a supportive community. Students check out mentally (faster than you can say “standardized test prep”), enrollment drops, and administrators conclude that arts programs simply can’t scale effectively.

But a larger program unlocks a new opportunity: diverse creative communities generate more innovation than isolated individual instruction.

How to Scale Without Losing Magic

Jack’s solution came from approaching his program the same way his colleagues who teach performance and ensemble classes build their groups.

The core principle of Jack’s music production classes are to open students up to the possibilities of music as a career. His Career Technical Education program lets students explore performance, audio engineering, being an agent, and other roles in the music industry. In performance classes, students naturally form close relationships through playing together. In music production classes, teachers need to reverse-engineer that ensemble feeling.

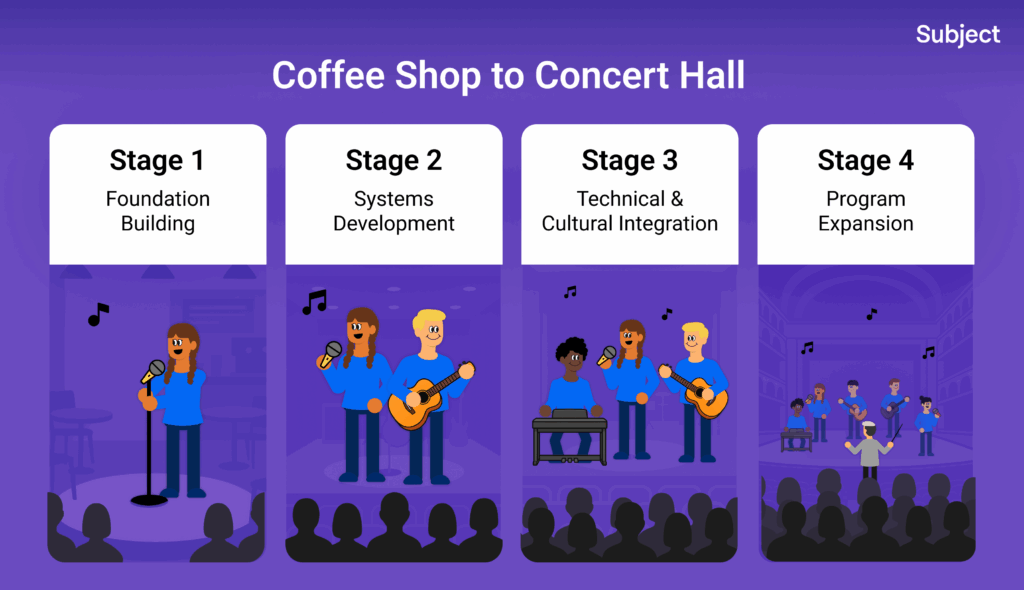

That’s because individual instruments (students) become more powerful when they harmonize with others. When you break out his process into four stages, it’s clear how to create peer learning systems that strengthen as programs expand.

Stage 1: Foundation Building

Social cohesion through peer collaboration: Rather than competing for teacher attention like contestants on “The Voice,” students become invested in each other’s success. Jack starts by creating structured opportunities for students to share their work in “symposiums,” or safe environments where peer feedback becomes as valuable as instructor guidance.

Genre freedom: Students bring their own musical backgrounds to the classroom: “I want students to bring their own funds of knowledge to my classroom whenever, wherever possible,” our music teacher explains. “If a student wants to make hyperpop, we’re gonna make hyperpop.” At the end of the day, not every creative project needs to sound like it was produced by the History Channel in 2004.

Stage 2: System Development

Mentorship systems: Jack identifies student leaders not by musical skill alone, but by their willingness to support peers. He explains that students who become leaders are often students who are going around the room, checking in on people, saying, “Hey, I heard your project the other day, it was really great.'” These aren’t the kids trying to be the next Grammy winner; they are the ones who actually remember other people exist.

Peer feedback structures: Students learn to give constructive criticism using Jack’s “comment, question, or suggestion” method. This structured language helps students provide meaningful feedback without falling into “roast culture” that shuts down creative risk-taking.

Stage 3: Technical & Cultural Integration

Hands-on technical mastery: Students master industry-standard tools like digital audio workstations while applying them to their chosen genres. The technical skills transfer across musical styles, but engagement comes from cultural relevance. In other words, students are given tools to create their favorite music, instead of being told to all practice “Hot Cross Buns” on the recorder for the thousandth time.

Showcase opportunities: Regular performance opportunities create deadlines and shared goals that build community investment. Jack’s music production program has a yearly showcase, and student volunteers in the program also take the lead on finding performance opportunities for young performers. Call it “peer pressure, but make it productive,” but students work harder when they know their peers will hear the results.

Stage 4: Program Expansion

Career pathway awareness: Students discover the full spectrum of music industry opportunities, from audio engineering to artist management. “There’s all these other avenues to enter the music industry,” he says, helping students see beyond the performer-or-bust mindset.

Student voice and choice: Mature programs become student-driven, with peer leaders managing studios, coordinating showcases, and mentoring newcomers. This distributes the workload while developing real-world leadership skills—like training a bunch of mini-CEOs, but with better taste in music.

Why Remote Creative Work Actually Works

Jack’s program started in COVID and continued because he’d already built remote creative collaboration into his teaching model:

“Students are able to invite each other into projects, and they’re able to jump in on the same project and work together. Instead of having students work in real time, live in the classroom, they could do so from the comfort of their homes.”

While it was certainly useful as a pandemic contingency plan, this hybrid model is actually how professional creative industries increasingly operate. Music production, film scoring, and content creation all rely on distributed teams collaborating across distances.

The tech enablement also democratizes access to high-quality creative tools. Browser-based digital audio workstations mean students don’t need expensive equipment at home to participate fully in program activities. This levels the playing field while teaching the same professional collaboration skills they’ll use in their music careers.

Arts Education Builds More Than Artists

Creative programs designed around peer mentoring scale, but they also develop the collaborative leadership skills every industry needs.

When students learn to give constructive feedback, manage creative projects, and support others’ artistic growth, they’re building transferable professional capabilities that work whether they end up on stage, in the tech booth, or in a boardroom.

“If you want to be in the music industry, I think you have to love music,” Jack reflects. This appreciation, combined with technical competency and collaborative leadership experience, creates graduates who can contribute meaningfully whether they become professional artists or bring creative thinking to other careers.

The stages of student involvement work because they honor both individual creative development and community building. It’s the exact combination that makes arts education uniquely valuable in developing human potential.

It’s not a choice between scale and soul. They can compose programs that amplify both, one student leader at a time.