Remember when your biggest teaching worry was whether you had enough copies of sheet music?

Those were simpler times.

Now you’re competing with Alix Earle for attention, managing 100+ students across different skill levels, and somehow supposed to honor every kid’s musical background from k-pop to Hamilton. Oh, and make it educational.

Jack Aron knows this feeling intimately.

As an Electives Lead at our virtual school and music production teacher at Culver City High School, Jack faced the ultimate test when COVID hit. His music program went from 20 students sharing instruments in a cramped room to over 100 students working individually on computers. The challenge is more philosophical than technical.

“How do we make this still work?” he wondered. “How do students develop this social cohesion that they had in ensembles, but virtually?”

Six years later, Jack’s program spans multiple course levels, partnerships with Sony Films, and graduates who sign record deals. His solve wasn’t abandoning student choice, but rather creating structured lessons that made diverse creative expression possible at scale.

The Binary Trap Most Teachers Fall Into

When building creative programs, most teachers think they have to maintain strict curriculum control or give students creative freedom and watch chaos ensue.

Jack encountered this dilemma when his program started growing beyond what he could manage with individual attention.

The traditional music education model works well for ensembles: everyone plays the same piece, follows the same conductor, achieves the same goal. But when students work on individual creative projects, this model falls apart. The music teacher said some students thrive with complete freedom, while others freeze up when given too many options.

“You don’t want to give them so much that they don’t even know what they want to do.”

The scaling challenge becomes even trickier when students bring vastly different musical backgrounds. Jack’s classes include students who want to make hyperpop, hip-hop, classical compositions, and video game soundtracks—sometimes all in the same room. Most teachers either force everyone into the same genre (killing authentic student voice) or let everyone do whatever they want (abandoning educational standards).

Jack did away with choosing between structure and freedom. Instead, he created the right kind of structure—one that actually enabled more creative expression, not less.

Constraints That Spark Creativity

Jack’s counterintuitive insight: students need clear technical boundaries to express their authentic creative voices.

“I have a very clear framework of what I want them to do,” he says. “I want them to build a project that paces out the material properly and appropriately. But how they go about doing it through their various cultures, genres, or styles of music that they like is totally up to them.”

This approach sits between rigid traditional music education and completely unstructured creative time. Instead of telling students what to make, Jack gives them technical challenges that can be solved in multiple ways.

The genius lies in making the constraints about musical concepts rather than musical styles. “I may want students to make a project that’s in a binary form,” Jack explains. “So binary would mean that there’s an A section and there’s a B section. Now, however a student chooses to do said A section and B section is totally up to them.” A student can explore this through trap beats, jazz piano, or orchestral composition. The learning objective stays the same, while the creative expression remains authentic to each student’s interests.

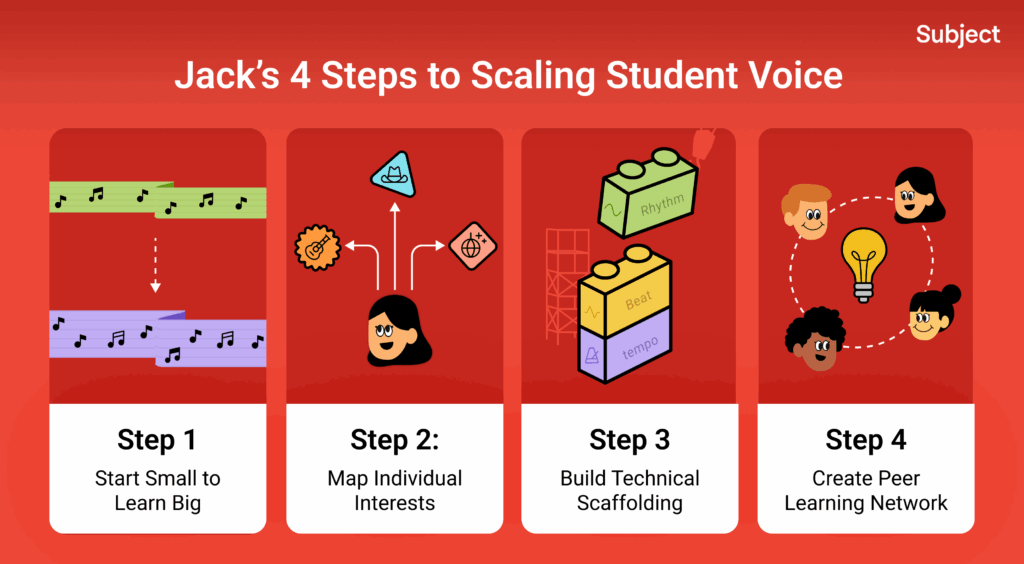

Jack’s 4 Steps to Scaling Student Voice

- Step 1: Start Small to Learn Big

Jack begins every semester with “The Ringtone.” It’s a deceptively simple assignment that reveals everything he needs to know about his students’ creative instincts. “I’m only giving them 30 seconds to a minute to create a piece of music however many tracks they want,” he explains. “I want to see if they can hold my attention for that long.”

The constraint is tight—time limits, specific tools, clear objective—but the creative freedom is complete. “Some students go for maximalism, they’re like, I’m gonna throw 100 soundbites in this,” Jack recalls. “Where some students are like, ‘I’m gonna do two things: make a drumbeat, and make a little cool chord line.’”

This controlled environment eliminates choice paralysis while giving Jack insight into how each student thinks about music-making. The short format makes feedback manageable at scale, and the constraint ensures everyone can complete the assignment regardless of experience level.

- Step 2: Map Individual Interests Through Investigation

Once Jack understands each student’s creative instincts from the initial project, he begins building individual profiles. “For me as the teacher, I’m interviewing them. I’m asking them questions, like, what do you like? Or what… how did that sound to you?”

This isn’t a simple survey about favorite genres. Jack digs deeper, asking about gaming music, movie soundtracks, family music, and any audio they engage with regularly. The goal is understanding not just what they like, but how they think about sound and what roles interest them—production, composition, audio engineering, live sound.

“Sometimes it takes until the end of the first semester, even, to really know what a student’s all about, musically, and what they want to make,” Jack admits. Some students discover they’re more interested in supporting other people’s creativity through audio engineering than making their own music. Jack makes room for these discoveries.

“There’s always a place for you in my classroom,” he adds, referring to these students. “You don’t have to be the best music maker and you don’t have to be the top dog producer.”

- Step 3: Build Technical Scaffolding With Multiple Expression Paths

“We definitely start with the sort of same framework and rubric,” Jack says.

With student interest profiles mapped, Jack creates learning objectives that can be achieved across multiple genres and styles. The key insight: chord progressions work in both country and hip-hop, arrangement principles apply to classical and electronic music, audio engineering concepts transfer across all styles.

This lets Jack assess technical skill development rather than stylistic preferences. A student working in death metal learns the same arrangement concepts as someone creating ambient soundscapes. The rubric focuses on understanding of musical theory, not genre conformity.

- Step 4: Create Peer Learning Networks

The final step makes large-scale individual attention possible: training advanced students to support their peers.

“I’m now telling my own students who are becoming leaders within the program, ‘hey, these are some freshman producers who just joined my class, listen to their projects. Don’t just immediately critique it, listen to what they’re saying, what music they’re making, and tell them that they’re doing a good job.’”

Jack identifies student leaders not just by technical skill, but by their willingness to support their peers. He trains them to give structured feedback using a “comment, question, or suggestion” format that keeps critiques constructive and specific.

Regular “symposiums” where students share work create the social cohesion that traditional ensembles provide naturally. “If a beat drops and all the kids are like, ‘whoa,’ that excitement becomes the new social cohesion—the camaraderie of sharing projects with each other.”

Students Drive Their Own Learning

Jack’s program grew from 20 students to over 100 across multiple course levels, with students pursuing diverse pathways from audio engineering to composition to music business.

Jack’s success also goes far beyond the classroom:

- Recent graduate Lily Sturgis won Spotify’s Young Producers Beat Battle and signed a record deal

- Students regularly collaborate with film and game design departments

- Some students even ended up scoring movies that premiere at Sony Films

But the most telling metric is Jack’s observation about individual growth:

“I’ve just watched them grow from a novice producer into a fully professional producer within the span of a year. It’s almost unbelievable to me.”

Students develop both technical competency and unique creative voices because they’re motivated by personal interest. The structured framework ensures they meet educational standards, while the creative freedom keeps them engaged and authentic.

The peer learning system creates a sustainable way to provide individual attention at scale. Advanced students become invested in the program’s success, creating a culture where supporting others’ creativity becomes part of the learning process itself.

Jack’s four-step method proves that structure and creative freedom aren’t mutually exclusive but rather complementary. When done right, clear constraints don’t limit student voice; they amplify it. The trick is making sure those constraints serve the students’ creative development rather than the teacher’s convenience.